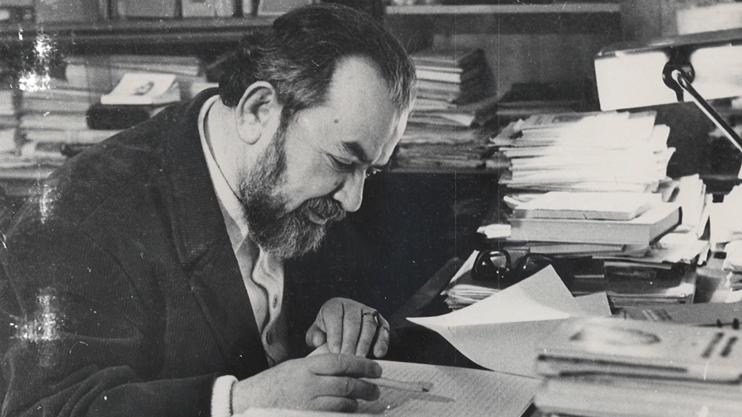

This year is the hundredth birth anniversary of Gevorg Emin, one of the fine names of the poetry of Armenia in the second half of the past century, along with Hamo Sahian, Hovhannes Shiraz, Silva Kaputikian, Hrachia Hovhannisian, and especially Paruyr Sevak, who took the mantle after the death of Yeghishe Charents during the Stalinist purges.

He was born Gevorg Muratian on September 30, 1919, in the town of Ashtarak. He was forced to adopt the name Karlen in the 1930s, at a time when there was the so-called “Communist baptisms.” In 1940 he graduated from the school of Hydrotechnics of the Polytechnic Institute “Karl Marx” of Yerevan (now the State Engineering University of Armenia). However, he soon shifted to literature and in the same year published his first book of poetry, Initial Path, in 1940, which he signed Gevorg Emin. He worked from 1940-1942 at the Matenadaran and in the district of Vardenis. He was wounded during his participation in World War II from 1942-1944.

Emin went to study at the studio of Armenian writers, which was attached to the Literary Institute of Moscow, from 1949-1950. He returned to Armenia and became the Yerevan correspondent of the Moscow literary weekly Literaturnaya Gazeta (1951-1954). In 1951 he won the State Prize of the Soviet Union for his collection New Road, published two years before. In 1954 he was back to the Soviet capital and studied until 1956 in the higher literary courses adjunct to the Writers Union of the Soviet Union.

In the Stalin years, Emin had started finding his own voice amid ideological restraints and criticism. His poetry, where the reflections on humanity, his people, and the homeland were matched with a more free style in composition, gained critical attention from the 1960s. Between 1968 and 1972 he was the editor in chief of the monthly Literaturnaya Armenia, published by the Writers Union of Armenia in Russian. Afterwards, he entered the Institute of Art of the Academy of Sciences as a senior researcher. In 1976 he won the State Prize of the Soviet Union for the second time after the publication of his book Land, Love, Century, and in 1979 he won the prize “Charents” in Armenia.

Besides a steady flow of poetry, published in some two dozen books, Emin was also a prolific author of essays, which were collected in several volumes, including Seven Songs about Armenia (1974), the most popular. The latter was derived from his script for the homonymous film, shot in 1967 by Grigor Melik-Avakian, which earned prizes in festivals in Yerevan and Leningrad (St. Petersburg). He was a prolific translator and gathered his best works in Book of Translations (1984). At the same time, his poetry was translated into many languages, including English (Land, Love, and Century, 1988).

Gevorg Emin was always a non-conformist writer, and his essays published in the twilight of the Soviet regime and in the first years of independence brought new elements to understand the immediate past. He passed away on June 11, 1998, at the age of seventy-eight.

Showing posts with label Stalin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Stalin. Show all posts

Monday, September 30, 2019

Thursday, August 1, 2019

Death of Alexander Bekzadian (August 1, 1938)

Like many of his compatriots involved in communism, Alexander Bekzadian came to believe that socialism (morphed into communism) was the only salvation for Armenians, and did not view the issue of the Armenian liberation struggle as such. Led by the winds of world revolution, they called upon Armenians to fight against world imperialism along foreign socialists.

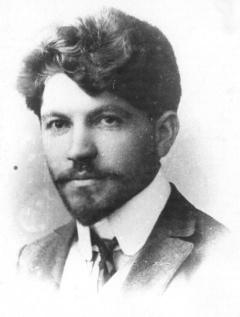

Bekzadian was born in 1879 in Shushi, the capital of Artsakh (Gharabagh), in the family of a judicial officer. Family well-being allowed him getting a brilliant education. In 1897 he graduated from the Royal School of Shushi, one of the best educational institutions in Transcaucasia at the time, and entered the School of Agriculture at the Polytechnic Institute of Kiev. In 1901 he became a member of the Social-Democratic organization of the University of Kiev, and two years later, the Bolshevik fraction of the Russian Social-Democratic Party. He was expelled from the university and the city for his political activities. He went straight to Baku, where his family had moved, and continued his activities within the local Bolshevik committee. His was a family of heightened political engagement; his sisters Mariam and Elena would later adopt the ideas of the Russian revolution, two of his brothers, Tigran and Hovsep, would be ARF members, and Ruben, member of the Social-Revolutionary party.

In 1905 he was arrested and imprisoned. However, he escaped and became an exile in Switzerland from 1906-1914 with an active political life as a sort of linchpin between the Caucasian Bolsheviks and the leader of the party, Vladimir Lenin. He entered the Law School of the University of Zurich, where he defended his doctoral dissertation in 1912.

Bekzadian was allowed to return to Russia in 1915, but was arrested when he rushed to Baku and remained in jail until the Russian Revolution of February 1917. After being released, he went back to Baku, where he became president of the provincial Food Committee. In 1918 he moved to the northern Caucasus and the following year he was a member of the Caucasian Committee of the Bolshevik Party. He was actively engaged in the struggle against the “bourgeois” Republic of Armenia and became one of the organizers of the failed Communist uprising of May 1920.

Bekzadian was a member of the Revkom, the Bolshevik committee that proclaimed the Sovietization of Armenia, and Popular Commissar of Foreign Affairs and Supplies in the first government of Soviet Armenia. In December 1920 and January 1921 he demanded from the Kemalist government of Turkey to stop the atrocities against the Armenian population in the areas occupied by Turkey and start negotiations to return Kars and Alexandropol to Armenia. However, the Armenian delegation led by Bekzadian was excluded from the negotiations started in Moscow in February-March 1921 by Turkish demand, giving the rebellion of February 1921 as pretext. He was reinstated in his position after the end of the rebellion in April. However, he failed to obtain any meaningful result at the time of the Treaty of Kars, which consecrated the loss of Kars, Ardahan, Mount Ararat, and Ani to Turkey in October 1921.

In 1922 Bekzadian abandoned Armenia and took a secondary position at the commercial mission of the USSR in Berlin for the next four years. From 1926-1930 he was designated deputy president of the Council of Popular Commissars of the Transcaucasian Federation and Commissar of Commerce. Afterwards, he returned to foreign affairs: from 1930-1937 he was Soviet ambassador, first to Norway until 1934, and then to Hungary. He abandoned his diplomatic activities in 1937 and returned to Moscow.

Like many veteran Bolsheviks, Alexander Bekzadian was a victim of the Stalinist persecutions. In 1938 he was charged with being a Trotskyite and having engaged in anti-governmental activities. After months of trial, he was executed on August 1, 1938, at the infamous Communarka shooting ground of the NKVD (a predecessor of the KGB), which functioned from 1937 to 1941 with more than 10,000 people killed and buried there. Like millions of Stalin’s victims, he was posthumously rehabilitated.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Death of A. Amatuni (July 28, 1938)

He

was simply known as “Amatuni” when he briefly showed up at the top

echelons of Soviet Armenia in the 1930s, but his name became infamous

for those who are acquainted with the horrors of Stalinism.

As

an irony of history, his actual name was Amatuni Vardapetian, so he

descended from a doctor of the Church. There were several Bolshevik

militants whose last names show a religious connection, and they would

become its greatest persecutors.

Amatuni

was born on October 24, 1900, in Elizavetpol (Gandzak, nowadays Ganja),

in the region of Lower Gharabagh. His biography is relatively sketchy.

He became a member of the Communist Party in 1919, and probably at this

time he adopted his first name as his last name.

After

working in some positions of leadership within the Communist Youth,

Amatuni studied at the Institute of Red Professorship in Moscow

(1926-1928) and then returned to Armenia, where he was head of the

department of propaganda of the Central Committee of the local Communist

Party, then secretary of the provincial committee of Yerevan and of the

Central Committee itself. He later moved on and from 1931-1935 he

worked in Tbilisi and Baku in similar positions.

Meanwhile,

the death of veteran Bolshevik Sergei Kirov, assassinated in Leningrad

(St. Petersburg) in December 1934, was a signal for the repression of

the following years, as it was ascribed to a mythical “right-Trotskyite”

center. The latter supposedly responded to Lev Trotsky, who had been

expelled from the Soviet Union following his defeat in the power

struggle with Stalin. A special committee created during the 20

th

Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 noted in

its report that from 1935-1940 a total of 1,635,000 people had been

arrested for anti-Soviet activities, of which 688,503 were shot to

death. Almost ninety percent of those arrests happened in the period

1937-1938.

Amatuni,

a henchman of Stalin’s right hand in the Caucasus, Laurenti Beria, was

sent back to Armenia as second secretary of the Central Committee from

1935-1936. The repression started in Armenia with the arrest of Nersik

Stepanian, director of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, in May 1936.

Stepanian was charged as the leader of the “right-Trotskyite” center,

which supposedly aimed at ending the Soviet rule in Armenia, separating

the country from the Soviet Union, and declaring independence, and shot

in July 1937. On July 9, Aghasi Khanjian, first secretary of the Central

Committee, was summoned to Tiflis for a meeting with Beria and

committed “suicide” (many decades later, it was found out that he had

been murdered by Beria himself). On the day of his burial, July 12,

there was a meeting of the “party active,” where 23 participants

declared that Khanjian was a traitor, chauvinist, sponsor of

anti-revolutionary elements, and so on and so forth. He was replaced

with Amatuni, who unleashed a series of arrests of party members,

intellectuals, clergymen, members of the military, et cetera, with false

charges orchestrated by Khachik Mughdusi (Astvatzatrian), Commissar

(minister) of Internal Affairs.

This

first wave of repression, which lasted until September 1937, included

many former party leaders in Soviet Armenia and even many veterans of

the sovietization period in 1920-1921. Many famous writers, like

Yeghishe Charents, Axel Bakunts, Gurgen Mahari, Vahan Totoventz, Zabel

Essayan, and others were also among those who were summarily condemned

to death and shot, died in prison, or were sent to exile in Siberia.

The

repressors soon became the repressed. The second wave would start with

the plenary session of the Central Committee on 20-22 September 1937,

with the leading participation of Beria from Tiflis, and Georgi Malenkov

and Anastas Mikoyan from Moscow. Amatuni, who had been hailed on

September 5 in the party newspaper

Khorhrdayin Hayastan

as

the one who had helped disclose the “wreckers,” was accused of having

become the new leader of the “right Trotskyite center” and arrested

during the plenary, together with Stepan Akopov, second secretary of the

Central Committee, and Mughdusi. He was replaced with Beria’s protégé

Grigori Arutiunov, who would last until the death of Stalin and the fall

of Beria in 1953.

Nikolai

Yezhov, head of the NKVD (the predecessor to the KGB) from 1936-1938,

addressed a letter marked “secret” to Stalin on September 22, 1937. He

wrote: “Comrade Mikoyan asks to allow shooting a supplement of 700

people with the goal of cleaning Armenia from anti-Soviet elements . . .

I suggest to shoot 1,500 people, for a total of 2,000 people including

the previously approved number.”

From

1937-1938, a total of 8,104 people became victim of the repression,

including former members of the three Armenian parties (Armenian

Revolutionary Federation, Hunchakian Party, and Ramgavar Azadagan

Party), and of Socialist parties. The list shows that 3,729 were

indicted for anti-Soviet activities, 1,333 for A.R.F. activities, 508

for anti-revolutionary activities, 109 for being Trotskyites, and 9 for

chauvinist activities. Almost sixty per cent of the victims of

repression (4,530 people) were shot.

Seventy-one

of the 106 participants in the “party active” meeting of July 12, 1936,

were subsequently liquidated, as well as many executors and witnesses

of the crimes committed from 1936-1937. Among them was Amatuni, who was

shot in Moscow on July 28, 1938.

Monday, June 25, 2018

Birth of Levon Orbeli (June 25, 1882)

Levon

(also known as Leon) Orbeli was the middle brother in a family of scientists and

an important physiologist, mostly active in Russia, who made important

contributions to this discipline.

Orbeli

was born in Darachichak (nowadays Tzaghkadzor), in Armenia, on June 25, 1882. He

was the brother of archaeologist Ruben Orbeli (1880-1943) and orientalist Hovsep

(Iosif) Orbeli (1887-1961). The family descended from the princely Orbelian

family, which ruled over the region of Siunik between the thirteenth and

fifteenth centuries.

The

future scientist graduated from the Russian gymnasium in Tiflis in 1899 and

continued his studies at the Imperial Military-Medical Academy of St.

Petersburg. He was still a second-course student, when he started working in the

laboratory of famous physiologist Ivan Pavlov in 1901, the same year when Pavlov

developed the concept of conditioned reflex. Orbeli's life and scientific career

would be closely connected with Pavlov’s work for the next thirty-five years.

The

future scientist graduated from the Russian gymnasium in Tiflis in 1899 and

continued his studies at the Imperial Military-Medical Academy of St.

Petersburg. He was still a second-course student, when he started working in the

laboratory of famous physiologist Ivan Pavlov in 1901, the same year when Pavlov

developed the concept of conditioned reflex. Orbeli's life and scientific career

would be closely connected with Pavlov’s work for the next thirty-five years.

He

graduated from the Military Medical Academy in 1904 and became an intern at the

Naval Hospital in the Russian capital. He joined Pavlov as his assistant in the

Department of Physiology at the Institute for Experimental Medicine from 1907 to

1920. He was sent abroad to do research from 1909-11, working in Germany,

England, and Italy.

Afterwards,

Orbeli occupied many top positions in the Russian scientific world. He was head

of the laboratory of physiology at the P. F. Lesgaft Scientific Institute in

Leningrad (the new name for St. Petersburg during the Soviet times) from 1918 to

1957. Meantime, he was professor of physiology at the First Leningrad Medical

Institute (1920-1931) and at the Military-Medical Academy (1925-1950), which he

also directed from 1943 to 1950.

In

1932 he entered the USSR Academy of Sciences as corresponding member and was

elected academician in 1935. After Pavlov’s death, Orbeli became Russia’s most

prominent scientist. He developed a new scientific discipline, evolutionary

physiology, consistently applying the principles of Darwinism. He devoted

particular attention to the application of the principles of evolution to the

study of all the nervous subsystems in animals and man. He promoted the study of

human physiology, especially vital activity under unusual and extreme

conditions. His more than 200 works on experimental and theoretical science

included 130 journal articles.

Levon

Orbeli was director of the Institute of Physiology of the Academy (1936-1950)

and of the Institute of Evolutionary Physiology of the USSR Academy of Medical

Sciences (1939-1950), where he was elected academician in 1944. He served as

vice-president of the USSR Academy of Sciences (1942-1946), where he founded and

headed the Institute of Evolutionary Physiology in 1956. He was an academician

of the Armenian Academy of Sciences in 1943 (his brother Hovsep was the founder)

and had an important legacy in the development of physiology in Armenia. The

Institute of Physiology of the Academy of Sciences carries his

name.

He

received many honors for his extraordinary scientific work. He was member of

many foreign societies and earned the State Prize of the USSR (1941) and two

important prizes of the Soviet Academy of Sciences In 1937 and 1946. He was

bestowed with many decorations, including the title of Hero of Socialist Labor

in 1945.

In

the last years of Stalin’s life, sciences became the target of state repression.

At a joint session of the USSR Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Medical

Sciences in 1950, the official doctrine of “Pavlovism” was promulgated and many

prominent physiologists, including Orbeli, were denigrated and blamed for being

non-Marxists, reactionaries, and having Western sympathies. Like many others who

were victim of these political games, Orbeli would be rehabilitated after the

death of Stalin in 1953.

In

the last years of Stalin’s life, sciences became the target of state repression.

At a joint session of the USSR Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Medical

Sciences in 1950, the official doctrine of “Pavlovism” was promulgated and many

prominent physiologists, including Orbeli, were denigrated and blamed for being

non-Marxists, reactionaries, and having Western sympathies. Like many others who

were victim of these political games, Orbeli would be rehabilitated after the

death of Stalin in 1953.

He

passed away on December 9, 1958, in Leningrad, where he was buried. A museum in

the town of Tzaghkadzor (Armenia), inaugurated in 1982 (picture), on the centennial of

Levon Orbeli’s birth, is dedicated to the three Orbeli brothers.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

Deportation to Altai (June 14, 1949)

The

great wave of repression of 1936-1938, which cost the lives of millions of

Soviet citizens, had several thousands of victims in Armenia, including many

people who were exiled to Siberia. During and after World War II, a second, less

well-known wave would shatter many areas of the Soviet Union, including

Armenia.

The

preparations, in utmost secrecy, started in January 1949. By command of the

Ministry of State Security of the USSR, lists of former Armenian Revolutionary

members (Dashnaks),

former war prisoners and members of the Nazi-sponsored Armenian Legions,

repatriates, and their families were prepared.

On

May 28, 1949, the ministry gave the order, and the next day, the USSR Council of

Ministers, with Stalin’s signature, approved the “extremely secret” resolution

No. 2214-856: “On the transportation, repopulation, and work allocation of those

expelled from the Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist

Republics, as well as the coastal areas of the Black Sea.”

A

group of high-ranking officials of the Ministry of State Security arrived in

Yerevan, led by Lieut.-Gen Yuri Yedunov, deputy head of the Second General

Committee. The latter was well experiences in these matters, since he had

managed the expulsion of the so-called families of “bandits and kulaks” of

Latvia (28,981 people) on March 25-28 of the same year.

On

the night of June 13-14, 1949, the unexpected happened. Both the locals, who

already knew the Stalin inferno, and the repatriates, who took pains to get used

to the whims of the totalitarian regime, were taken by surprise. Deportations

were common as punishment from the 1920s, but they had skipped Armenians so far.

That night, 2,754 families (12,300 people) were exiled from all regions of

Soviet Armenia to the Altai territory, in the southeast of Western Siberia.

Around twelve percent (1,578 people) of the deportees were repatriates. Of those

families, the greatest number came from Yerevan (461) and Echmiadzin (182).

Interestingly, the massive expulsion had no ethnic grounds; the deportees were

known by the label of “Dashnaks.” The targeted repatriates were those with

former Greek and Turkish citizenship.

They

were sent by train in cargo wagons, and traveled for about two weeks until they

were placed in the collective farms and state farms of the Altai region, without

knowing why they were moved and what their fault was. The mass deportation was

legalized much later, from November 1949-June 1950. A special committee adjunct

to the Ministry of State Security prepared documents in the name of the elder of

the exiled family or the member of the family who was the cause for exile.

The

deportees were told that there was no return and they would stay there until

their death. They were warned about leaving their area of residence, which would

be penalized with 20 years of prison or forced labor. They had to present

themselves once a week at the guard’s office to sign papers that confirmed their

presence.

The

exiles wrote letters addressed to the highest hierarchy of the country (Stalin,

Beria, Malenkov, Voroshilov), as well as Grigor Harutiunian, First Secretary of

the Armenian Communist Party, asking for leniency and explaining that they had

committed no crime to deserve such a punishment. However, most of the time,

those letters were useless, and the response was standard: “Your issue is not

subject to review.”

The

exiled families were involved in lumbering or farming. Neither their education

nor their expertise counted. The repatriates, in particular, had big issues with

language, since they mostly did not speak Russian, and this complicated their

interactions at work and with the authorities. The children received their

education only in Russian.

After

Stalin’s death, the life of the exiled had some improvement. They were not

allowed to return, but they could make “illegal” movements within the region of

Altai, change their residence, find another job, et cetera. The authorities

started giving encouraging responses to the letters written after Stalin’s

death. A special commission was set up in 1954 to review the cases of the

deportees. In the next two years, they were absolved of their “crimes,” and by

1956 the overwhelming majority of the exiled families were back in

Armenia.

There

is very little documentation about this tragic episode of Soviet Armenian

history. It remained totally unspoken until the fall of the Soviet Union. Since

2006, June 14 is commemorated in the Armenian calendar as Day of Remembrance of

the Victims of Repression. A memorial complex to the victims of repression

during Soviet times was opened in Yerevan on December 3, 2008. Today there are

some 6,000 victims of repression from 1937 and 1949, and 8,400 descendants of

those victims living in Armenia.

Friday, March 16, 2018

Treaty of Moscow (March 16, 1921)

The

Treaty of Moscow was signed between Soviet Russia and Kemalist Turkey

on March 16, 1921. The Russian side yielded to most Turkish demands, and

signed a document that was utterly damaging to Armenia for the sake of

Russian-Turkish “friendship and brotherhood.”

The

treaty was the outcome of the second Russian-Turkish conference, held

in Moscow from February 26-March 16, 1921, with the participation of two

Russian (Georgi Chicherin, the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, and Jelal

Korkmasov) and three Turkish representatives (Yusuf Kemal bey, Riza Nur

bey, and Ali Fuad pasha). Stalin, the Commissar of Nationalities,

lobbied against any claim from Turkey that could put the Russian-Turkish

alliance in risk. In a letter to Lenin on February 12, 1921, he had

written: “I just learned yesterday that Chicherin really sent a stupid

(and provocative) demand to the Turks to clean Van, Mush, and Bitlis

(Turkish provinces with enormous Turkish supremacy) to the benefit of

Armenians. This Armenian imperialist demand cannot be our demand.

Chicherin must be forbidden to send notes to the Turks suggested by

nationalist-oriented Armenians.” The Bolsheviks sought to halt further

Turkish advance into the region. Weary from the ongoing Russian Civil

War, which was winding down, they had no intent of starting a new war.

Not

surprisingly, Chicherin refrained from his pro-Armenian position, and

declared during the conference that Russia would not insist about

passing the border to the west of the Akhurian (Arpachay) and the south

of the Arax rivers. This meant that the entire province of Kars and the

district of Surmalu (Igdir), which had never belonged to the Ottoman

Empire, would go to Turkey. The Turkish delegation additionally claimed

for the province of Nakhichevan, which historically had belonged to the

Armenian Province and then to the governorate of Yerevan under the rule

of the Russian Empire, to be put under Azerbaijani administration.

Thus,

the treaty of “friendship and brotherhood” between Soviet Russia and

Turkey recognized Turkish control over Artvin, Ardahan, Kars, and

Surmalu. The region of Adjara, with the port of Batum, was returned to

Soviet Georgia on the condition that it would be granted political

autonomy due to its largely Muslim Georgian population. (Adjara became

an autonomous republic within Georgia.) Turkey withdrew from

Alexandropol (nowadays Gumri) and a new border was established between

Turkey and Soviet Armenia, defined by the Arax and Akhurian rivers.

According to these new boundaries, Mount Ararat and the ruins of Ani

remained within Turkey.

The

treaty also stipulated that Nakhichevan would become an autonomous

entity under Azerbaijani protectorate. Azerbaijan obliged not to

transfer the jurisdiction to a third party, namely, Armenia.

Additionally, Turkey later acquired a small strip of territory known as

the Arax corridor, which had also been part of the governorate of

Yerevan. This corridor was located east of Surmalu, limited by the Arax

River to the north and the Lower Karasu River to the south. It was a

strategic strip of land that allowed Turkey to share a common border

with Nakhichevan and, consequently, Soviet Azerbaijan.

Both

signatory parties were internationally unrecognized, and thus were not

subject of international law, which made the treaty illegal and invalid.

The RSFSR, now under the guise of the Union of Soviet Socialist

Republics, was legally recognized for the first time in 1924 by Great

Britain. The Great National Assembly of Turkey was a non-governmental

organization led by Mustafa Kemal, which did not have any legal grounds

to represent the Turkish state in international relations. According to

the Ottoman Constitution, only the sultan had the right to engage other

states, be it personally or through a representative. The Kemalist

movement was actually a rebellion against the legal authorities of the

country, and Kemal was a criminal fugitive who had been sentenced to

death by a fatwa signed by the Sheikh-ul-Islam, the highest religious

authority of the Ottoman Empire, on April 11, 1920, and a court-martial

on May 11, 1920.

The

section of the Treaty of Moscow related to Armenia was a violation of

international law, since treaties can only refer to the signatory

parties and do not create any obligation to third parties that are not

bound by treaty without the latter’s agreement. At the time of the

Treaty, the Soviet regime had been thrown out from Armenia by the

popular rebellion of February 1921.

The

treaty was reaffirmed in October 1921 with the Treaty of Kars and the

borders it established have been maintained ever since. However, this

did not mean that Soviet policymakers necessarily accepted the terms of

the treaty as permanent. After World War II, when the Soviet Union was

at the zenith of its power, its leader Stalin reopened the issue on

behalf of Armenia and his native Georgia. Supported by Moscow, both

republics began to assert territorial claims against Ankara. According

to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin made this move at the

insistence of Lavrenti Beria, the deputy premier and a fellow Georgian.

Indeed, Ankara sought the support of Washington, which had become

suspicious of Soviet intentions with the onset of the Cold War. The

issue was eventually dropped by Moscow and by 1952 Turkey joined NATO,

precluding any further discussion on border revisions.

The

frontiers established by the 1921 treaty remained unaltered and were

maintained by the newly-independent states of Russia, Georgia, Armenia,

and Azerbaijan after the dissolution of the U.S.S.R.

Following

the shoot down of a Russian plane over the Syria–Turkey border in

November 2015 and the rise of Russo-Turkish tensions, members of the

Communist Party of Russia proposed the nullification of the Treaty of

Moscow. Initially, the Russian Foreign Ministry considered this action

in order to send a political message to Turkey.

However, Moscow ultimately decided against it in its effort to de-escalate tensions with Ankara.

Friday, December 22, 2017

Death of Mekertich Armen (December 22, 1972)

Mekertich

Armen was a less known, even though well-regarded member of the

generation of Armenian intellectuals that became victim of Stalinism.

He

was born Mekertich Harutiunian on December 27, 1906, in Alexandropol

(nowadays Gumri), in a family of artisans. He studied in a local school

and then in the gymnasium for boys and in one of the schools opened by

the Near East Relief in the city. Years later, he would graduate from

the State Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, where he studied at the

section of script writing for two years.

In

1922-1923 he was a boy scout (scoutism was still tolerated in Soviet

Armenia in the early 1920s), and in 1923 published his first poem in the

local newspaper

Panvor

.

In 1925 Mekertich Armen was one of the founding members of the

short-lived “October” union of writers of Leninakan (Gumri’s name in

Soviet times), started by Gurgen Mahari (1903-1969) along with Soghomon

Tarontsi (1904-1971), Gegham Sarian (1902-1976), Sarmen (1902-1980), and

others. In 1925 he moved to Yerevan and entered another short-lived

union of writers, called “November” and founded by Yeghishe Charents

(1897-1937). He worked for a few years in the editorial offices of the

journals

Grakan Dirkerum

and

Yeritasard Bolshevik

. He would also be the secretary of the artistic council of Haykino (the Armenian film studios, later known as Armenfilm).

By

1934, when he became a member of the newly founded Writers Union of

Armenia, Mekertich Armen had already published several books of prose,

among them the novels

Yerevan

(1931) and

Scout 89

(1933).

His remarkable novel

The Fountain of Heghnar

(1935), set in pre-Soviet times, put him among the best writers of his generation.

However,

the political purges that swept the Soviet Union in 1936-1938 did not

spare the political and intellectual class of Armenia. Along with many

members of his generation (Charents, Axel Bakunts, Gurgen Mahari,

Vagharshag Norents, Soghomon Tarontsi, among many others), Mekertich

Armen was arrested in 1937 as an “enemy of the people” (the usual slogan

of authoritarian and totalitarian regimes to tarnish its potential and

real opponents) and exiled to a labor camp, where he remained until

1945.

Upon

surviving the hardships of exile, he returned to Yerevan and continued

his literary activities. He published new novels and collections of

short stories, but none repeated the success of

The Fountain of Heghnar,

which

had been printed twice before his arrest and had three more editions

from 1955 to 1961. In the short interlude of Nikita Khruschev’s period

of the “thaw,” when the crimes of Stalin were denounced and some works

reflecting the Siberian labor camps were allowed to be published, Armen

published a collection of short stories,

They Asked Me to Deliver to You

(1964),

that brought some recognition once again. In the last years of his

life, he was named Emeritus Worker of Culture of Soviet Armenia (1967)

and his collected works were published in five volumes (1967-1971).

The Fountain of Heghnar

was

the subject of two films (“The Fountain of Heghnar,” Arman Manarian,

1971, Yerevan, and “The Spring,” Arby Ovanessian, 1972, Iran).

Mekertich Armen passed away on December 22, 1972, in Yerevan.

Friday, May 5, 2017

Death of Martiros Sarian (May 5, 1972)

Martiros Sarian, one of the two names of Soviet Armenian culture who earned the title of Varbed (Վարպետ “Master”), was the founder of a modern Armenian national school of painting.

Martiros Sarian, one of the two names of Soviet Armenian culture who earned the title of Varbed (Վարպետ “Master”), was the founder of a modern Armenian national school of painting. He was born into an Armenian family in Nakhichevan-on-Don (now part of Rostov-on-Don, Russia) on February 28, 1880. In 1895, aged 15, he completed the Nakhichevan school. He received training in painting at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1897–1903) and then worked in the studios of the noted painters Konstantin Korovin and Valentin Serov. Soon Sarian became a member of a group of Moscow symbolist artists, and he began exhibiting his brightly colored paintings. He had works shown at the Blue Rose Exhibit in Moscow.

He first traveled to Armenia in 1901, visiting the regions of Lori and Shirak, the convents of Etchmiadzin, Haghpat, and Sanahin, Yerevan, and Lake Sevan. His first landscapes depicting Armenia (1902-1903) were highly praised in the Moscow press.

In 1904-1907 Sarian created the watercolor series "Fairy Tales and Dreams." Some pieces of this cycle were exhibited first at the Crimson Rose exposition in 1904 in Saratov and later at the sensational Blue Rose exposition in 1907 in Moscow. Starting from 1908, Sarian completely replaced watercolor with tempera. During this period, he took an active part in the exhibitions organized by the magazine Zolotoye Runo.

From 1910 to 1914 he traveled extensively in Turkey, Egypt, northwestern Armenia, and Persia. These trips inspired a series of large, fresco-like works in which he attempted to communicate the sensuousness of the Middle Eastern landscapes. He also incorporated into a number of his paintings the Persian motifs he had seen in the Middle East. Like many Russian artists of the early decades of the 20th century, Sarian was greatly influenced by impressionism. He was also interested in the paintings of Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin, as can be seen in his use of areas of flat, simplified color.

In 1915 he went to Etchmiadzin to help refugees who had fled from the Armenian Genocide. In 1916 he settled in Tiflis (now Tbilisi) where he founded the Society of Armenian Artists with fellow painters Yeghishe Tateosian, Vardges Sureniants, and Panos Terlemezian.

He married Lusik Aghayan, daughter of writer Ghazaros Aghayan, in 1917. The newly married couple moved to Nor Nakhichevan, where Sarian continued painting. In 1920 he became director of the museum of Armenian Folklore in Rostov. In 1921 he moved to Yerevan with his wife and two children, Sarkis (future literary scholar) and Ghazar (future composer). He organized and became director of the museum of archaeology, ethnography, and fine arts (now the National Gallery of Armenia). He also participated in the establishment of the Yerevan Art College and the Artists Union of Armenia. In 1922 Sarian designed the coat-of-arms and the flag of Soviet Armenia, as well as the curtain of the First Drama Theater in Yerevan. In 1924 his works participated in the 14th Bienale of Venice. He was awarded the title of People’s Artist of Armenia in 1925.

From 1926–1928 he lived and worked in Paris, but 40 paintings, most of his work from this period, were destroyed in a fire on board the boat on which he returned to Armenia, where he lived until his death. He spent most of his career painting scenes, especially landscapes of the homeland, often employing the impressionist technique of vivid, dappled color to capture the effects of light. He also painted many floral still lifes, as well as portraits.

In the difficult years of the 1930s, he was criticized as a formalist, since his work did not fit the state-sponsored artistic ideology of socialist realism. Sarian’s creative work was removed from the context of world modern art. A dozen of his portraits, which represented figures who were victims of the Stalinist purges, were destroyed in 1937. His famous portrait of Yeghishe Charents, however, survived. Nevertheless, he managed to continue his work and come out of this period unscathed. In 1941 he won the State Prize for his design of Alexander Spendiarian’s opera, Almast.

|

| Portrait of Yeghishe Charents, by Martiros Sarian |

His work was subjected to new official criticism after World War II. Nevertheless, artistic freedom was more or less regained after the death of Stalin (1953), and Sarian returned to his traditional themes. His series of landscapes “My Homeland” won the State Prize in 1961. His 85th birthday was widely marked, and a documentary on his life and work was released in 1966, when he also obtained the State Prize of Armenia for the third time. The Martiros Sarian house-museum was opened in 1967, when his memoirs were also published. He was also elected as a deputy to the USSR Supreme Soviet several times and awarded the Order of Lenin three times, as well as other awards and medals. He was a member of the USSR Art Academy (1974) and the Armenian Academy of Sciences (1956).

Sarian continued his creative work almost until the end of his days. He passed away in Yerevan on May 5, 1972. He was buried at the Gomidas Pantheon, next to Gomidas Vartabed.

Sunday, January 15, 2017

Birth of Osip Mandelstam (January 15, 1891)

Osip

Mandelstam, a famous Russian poet, was the author of one of the finest

essays on Armenia in the twentieth century. His sojourn in the country

helped him end his poetic block during the years when Stalinism was in

the rise and his own life would end in a concentration camp.

Osip

Mandelstam, a famous Russian poet, was the author of one of the finest

essays on Armenia in the twentieth century. His sojourn in the country

helped him end his poetic block during the years when Stalinism was in

the rise and his own life would end in a concentration camp.Mandelstam was born to a wealthy Jewish family on January 15, 1891, in Warsaw (Poland), then part of the Russian Empire. Soon after his birth, his father, a leather merchant, was able to receive a dispensation that freed their family from the Pale of Settlement—the western region of the empire where Jews were confined to live—and allowed them to move to the capital Saint Petersburg.

Mandelstam entered the prestigious Tenishevsky School in 1900 and published his first poems in the school almanac (1907). After studying in Paris (1908) and Heidelberg (1909-1910), he decided to continue his education at the University of St. Petersburg in 1911. Since Jews were forbidden to attend it, he converted to Methodism and entered the university the same year, but did not obtain a formal degree. He formed the Poets’ Guild in 1911 with several other young poets. The core of this group was known by the name of Acmeists. Mandelstam wrote The Morning of Acmeism, the manifesto for the new movement, in 1913. In the same year, he published his first collection of poems, The Stone.

Mandelstam married Nadezhda Khazina (1899-1980) in 1922 in Kiev (Ukraine) and moved to Moscow. In the same year, he published in Berlin his second book of poems, Tristia. Afterwards, he focused on essays, literary criticism, memoirs, and small-format prose. His refusal to adapt to the increasingly totalitarian state, together with frustration, anger, and fear, took their toll and by 1925 Mandelstam stopped writing poetry. He earned his living by translating literature into Russian and working as a correspondent for a newspaper.

In 1930 Nikolai Bukharin, still one of the Soviet leaders and a “friend in high places,” managed to obtain permission for Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam for an eight-month visit to Armenia. During his stay, Osip Mandelstam rediscovered his poetic voice and was inspired to write both poems about Armenia and an experimental meditation on the country and its ancient culture, Journey to Armenia (published in 1933): “The Armenians’ fullness with life, their rude tenderness, their noble inclination for hard work, their inexplicable aversion to anything metaphysical and their splendid intimacy with the world of real things – all of this said to me: you’re awake, don’t be afraid of your own time, don’t be sly.” As poet Seamus Heaney, winner of the Nobel Prize of Literature, wrote in 1981, “The old Christian ethos of Armenia and his own inner weather of feeling came together in a marvelous reaction that demonstrates upon the pulses the truth of his belief that ‘the whole of our two-thousand-year-old culture is a setting of the world free for play.’ Journey to Armenia, then, is more than a rococo set of impressions. It is the celebration of a poet’s return to his senses. It is a paean to the reality of poetry as a power as truly present in the nature of things as the power of growth itself.”

Mandelstam was ferociously criticized in Pravda for failing to notice “the thriving, bustling Armenia which is joyfully building socialism” and for using “a style of speaking, writing and travelling cultivated before the Revolution,” meaning that it was counterrevolutionary.

In November 1933 Mandelstam composed the poem “Stalin Epigram” (also known as “The Kremlin Highlander”), which was a sharp criticism of the climate of fear in the Soviet Union. He read it at a few small private gatherings in Moscow. Six months later, in 1934, he was arrested and sentenced to exile in Cherdyn (Northern Ural), where he was accompanied by his wife. After he attempted suicide, the sentence was reduced to banishment from the largest cities in European Russia, following an intercession by Bukharin. The Mandelstams chose Voronezh.

This proved a temporary reprieve. In 1937 the literary establishment began to attack Mandelstam, accusing him of anti-Soviet views. In May 1938 he was arrested and charged with “counter-revolutionary activities.” He was sentenced to five years in correction camps in August. He arrived to a transit camp near Vladivostok, in the far east of Russia, and died from an “unspecified illness” on December 27, 1938.

Like so many Soviet writers, after the death of Stalin, in 1956 Mandelstam was rehabilitated and exonerated from the charges brought again him in 1938. His full rehabilitation came in 1987, when he was exonerated from the 1934 charges. Nadezhda Mandelstam managed to preserve a significant part of her husband’s work written in exile and to hide manuscripts. She even worked to memorize his entire corpus of poetry, given the real danger that all copies of his poetry would be destroyed. She arranged for the clandestine republication of Mandelstam’s poetry in the 1960s and 1970s, and also wrote memoirs of their life and times, the most important being Hope against Hope (1970).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)